dscottsw

Was a former postulant monk in a Benedictine community and, while the life was not for me, have been fascinated by all things monastic ever since. Saw this advertised somewhere a couple of years ago, wrote down the title - and finally got around to getting the DVD. After the first five or ten minutes - you start wondering if the sound is broken on the TV, until it dawns on you that you are entering into The Great Silence. I was deeply moved by the brothers, old, young and in between who participated in this film. For someone who wants to get an experiential sense of monastic spirituality, in its most ancient form - this film is a wonderful opportunity. How amazing to convey so much, with almost no words. A Beautiful film.

gentendo

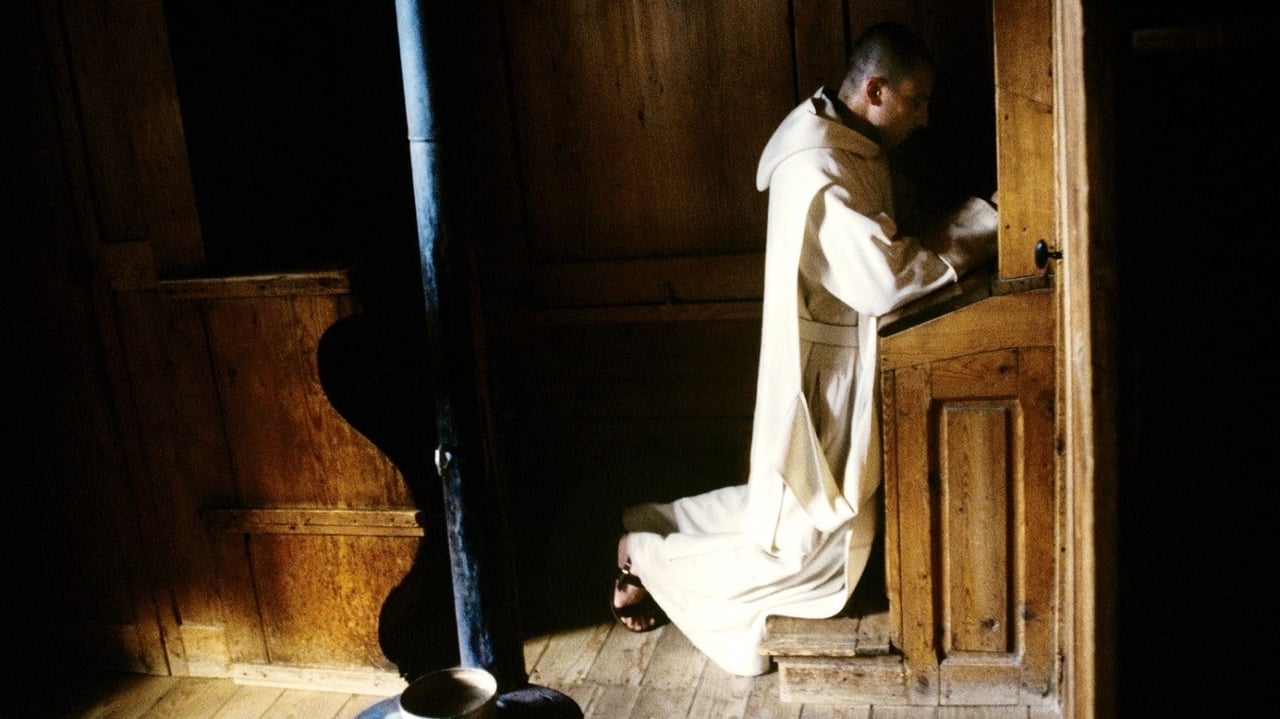

I believe the director's purpose in making this documentary was for a multiplicity of reasons. One in which was to reflect on the beauty and simplicity of an exceptional culture and in the process exalt the everyday. Another reason was to know that God is by stilling the soul with silence and pondering upon his words, as demonstrated in one of the explicit scriptures shown: "Allow the stillness to enter in and know that he is." The following evidence will support both efforts made by the director.Whereas most Hollywood or even some independent films make their aim at reaching a conclusion (often called a climax, or resolution), Into Great Silence is not concerned about reaching any destination. It is simply about process and duration. It is concerned with becoming an observerone who simply watches like a fly on the wall all of the events, activities, and services made explicit in the lives of real people. These people are not actorsthey do not live anywhere near the limelight. They are ordinary yet unique individuals that live extraordinary lives. The camera work helps reflect this extraordinary realism by persisting with long and sometimes tedious shots of the monks going about their daily activities. The lighting is rather significant too. There are no stage light set-upssimply all-natural. This choice by the director not only helps eliminate the man-made constructs of artificial lighting, but invites the viewer to become further absorbed in God's lightthe only natural light there is.The simplicity of each shot sometimes seems mundane, but then again, so is real life from time to time. There is a beautiful sequence captured of rain pouring into an open puddle outside that helps the viewer appreciate the simple yet profound beauties of the earth. An editing choice of minimal ellipsis portrays the time elapsed from season to season as well. This preference helped exalt the seasons we often take for granted and gave reason to why we ought to praise God for creating such amazing sights to behold.This idea leads to the next purpose of why the filmmaker undertook this project. The idea of God being found in the silence of nature is extremely important throughout the film. In fact, about 90% of it is silent. It begins with a renowned scripture found in the book of 1Kings, which reads something to the effect like, "And the earthquake rent the mountain in twain, but God was not in the earthquake. Then came the fires but God was not in the fire. And then came the winds but God was not in the wind. And after all this came a still small voice, even the Holy Ghost." The idea of the Holy Ghost (God's voice) being represented as a still small voice gives definition to what this film is all about. Whereas the world would demand an astonishing vision or mind-blowing miracle to be converted to God's existence, the monks realized that it is in the depths of silence and solitude that God's spirit is able to commune with an open mind. The world, as is, is ridiculously noisy and hustled. The monks desire to retreat from it demonstrates their willingness to search after and discover God, as illustrated in another scripture shown: "You shall seek me with all your heart and I will allow myself to be found." An interesting symbol used in the film that brings out the idea of finding God in silence is portrayed through the use of the red candle burning brightly in the darkness. This image repeats itself multiple times to teach the viewer of the importance of being a light/influence unto a world of darkness. I believed this was to show how the silence of one's presence can strangely attract the mind of a darkened sinner. It is not through lip service that a person will be converted unto God, but through the actions one takes by being who they areas reflected through the silence and lives of these diligent monks.

tenshin-3

This week marks the release, at least in the U.S., of the documentary Into Great Silence, which takes us inside of the Grande Chartreuse Monastery in the French Alps and is the home of a group of Carthusian monks.Thankfully, filmmaker Phillip Gronig, has ignored every "rule" when it comes to making a documentary. Not counting the monks chanting of the Divine Office, in the 164 minutes of the film scarcely 10 minutes worth is devoted to dialog. There are no expository narrations nor even the customary music soundtrack that one would expect. Instead one is made privy to the rare opportunity to glimpse a world seldom seen outside of the order itself. It is deep, wonderful journey into the Great Silence of the monks life. A silence where the still, small voice of God can be heard.Modern lives, like ours, are often so full of noise, that the silence that we experience here can almost be overwhelming at times. After all, most of us try to fill each waking hour it seems with some distraction. Just look at the time we spend watching television or listening to the radio. It's almost, at least in my case, that we fear what the silence will say to us. Even our prayers are often so full of words that we can drown out what God has to say back to us. This film has echoed some of the feelings that I have been trying to come to grips with recently. It has reinforced that great need in me to listen. I am beginning to understand, slowly I might add, that the more I listen, both to God and to others around me, the more they have to say to me. So often I get caught up in trying to "say the right thing" that I end up using the time that other people are talking trying to think what I should say next. This is no more true than in my prayer life.The watching of this film has been something of a retreat for me. Where all of my desires, pleadings, and static that normally occupies my time with God was replaced. Replaced by the Great Silence."Oh Lord, you have seduced me. And I was seduced."Just as a side note, there is a second disc that accompanies the movie which has more background on the order along with a wonderful segment of the Night Office. The "extras" on this disc tell you just enough to where you will probably want to know more. A couple of excellent books in English that I can recommend are Halfway to Heaven by Robin Bruce Lockhart, the recent An Infinity of Little Hours by Nancy Klein Maguire, and Carthusian Spirituality the writings of Hugh of Balma and Guido De Ponte.

Chris Knipp

If you can sit still for the nearly three hours of this film, it's almost guaranteed to bring down your heart rate, maybe make you want to spend more time in the high mountains or in the snow or contemplating spring flowers in some isolated place. Into Great Silence (Die Große Stille) is a documentary of unusual austerity and beauty, like La Grande Chartreuse itself, the Carthusian order's central monastery high in the French Alps that German filmmaker Philip Gröning has recorded. His film is steeped in a unique atmosphere; there is no narration. To have provided any would have interrupted the prevailing silence that is characteristic of the place. This method -- the withholding of all commentary -- can work fine for a documentary, especially where there is a lot of dialogue, as in the recent, highly admired Iraq in Fragments; or where the activities shown are familiar, such as the classroom scenes so meticulously filmed in Être et avoir (To Be and to Have), an un-narrated chronicle of a rural French elementary school. But lovely and calming as Into Great Silence is, it preserves the atmosphere at the cost of failing to penetrate its subjects' inner lives. How well can we ever understand spirituality? But above all, how well can we understand it from visuals, without any words describing the inner experience? There are other specifics that Gröning, who was forced to work virtually alone and without any artificial light, chooses not to detail. A monk's life is rigorously organized, but here that schedule isn't specified. Editing flits about arbitrarily between shots of monks praying alone or in the chapel, external landscape shots; shots of wood being chopped, food being prepared or delivered to cells, snow being shoveled, robes being made, heads being shaved, books being read at cell desks. And there's an initiation ritual, plain chants, poetically blurry close-ups of candle flames or fruit. There's even a moment of laughter and high spirits when a group of younger monks slide down a hillside in the snow (in their boots, without skis or snowboards). Bells sound, and the monks bustle about from one activity to another, but according to what system is left to the imagination. In one shot a monk sits in front of a big desk strewn with bills and documents. He just stares at them. What does it mean? Several times the succession of scenes is interrupted with a short series of shots of individual monks staring into the camera, wordlessly, of course. There is one long shot of a monk who may be dying. He too stares into the camera. These moments are rather spooky. Despite the presence of prescription eyeglasses, shoe goo, electricity for lights and an electric razor in the "Razora" room -- even, despite wood stoves in the cells, the sighting of a single radiator -- the place has a thoroughly medieval feel, and that's spooky too. Every so often in large letters there is a saying of Jesus, such as "He among you who does not renounce all his possessions cannot be my disciple," flashed in French on the screen, as in a silent film, and these are repeated, randomly. But again, is this randomness appropriate in depicting a life that is anything but haphazard in its structure? After an hour the film shows that the monks, though they lead daily lives that are silent and isolated except for chapel services, do also get together on Sundays for a communal meal followed by a walk and a chat, rain or shine. When given this opportunity, they don't analyze the world situation. They discuss minutiae of the order's regulations. Later, a blind old monk with impressive down-drooping eyebrows is the only one to address the camera directly. He speaks of blindness and death, describing both as welcome gifts from God, one received, another still to come.There is a significant omission. This place, begun in the early eleventh century, rebuilt in the seventeenth, produces a famous liqueur whose sale supports it; but we don't see the monks doing this work. Gröning says the process is too complicated and would distract from the rest. Distract from what? From the effect he wants to create; not from a picture of what the place is about. Gröning underlines the uniquely rare opportunity he's sharing with us by explaining at the end that he asked for permission to film in 1984, but was held off from doing so till 2000. Maybe he thought since he had to wait so long, he should make a long film. But the extra time doesn't mean deeper insight. At most it is the prolongation of a mood. Rather it seems an outgrowth of the random editing system, an unwillingness or inability to cut or to organize. Off-putting and tight-lipped though this film is, it will no doubt stand as one of the more distinctive of recent documentaries. But it inspires as much irritation as reverence. It's not utterly clear that Gröning is the ultimate guide to this world -- or to any world, for that matter.There are many paradoxes and ambiguities in a monastic existence. The Carthusian order is austere. Its life is one of renunciation and penitence. In this austerity there is a certain luxury. The monks choose it willingly. If they can stick with it (many apparently don't), it is what they want, an ideal setting for the uninterrupted contemplation of God. And it is a peaceful life, a safe life, a life cut off from the worries of cities and families and all uncertainty. Monks don't prepare their weekday meals in their cells any more; they're brought on a cart. Bare and spare and strict though it is, La Grande Chartreuse is in some sense the most spectacular of grand hotels.

AD

AD