Tyson Hunsaker

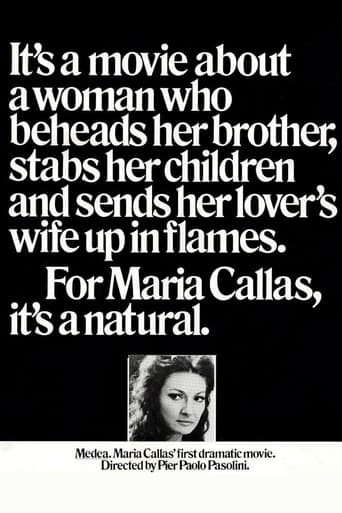

Medea feels like one of Pier Pasolini's more obscure and lesser known works. Being overshadowed by some of his heavyweights and more controversial films, Medea can be easily forgotten and tossed aside. This is unfortunate seeing how unique this film feels. What feels riveting about Medea is one: our lead's performance is outstanding. She plays Medea with utmost confidence and terror that paints a memorable portrait of a character that's unforgettable. Two: while camera work seems to break necessary rules, the audience feels unusually drawn to what's inflame due to great locations, excellent production design for its time, and it's dramatic dialogue. Unfortunately the dialogue does feel too good on paper and nowhere else which can take the viewer out of the experience. Like something written as a novel first which wasn't meant to be adapted in the first place. The film explores fascinating themes like jealousy, betrayal, relationships, etc. The story explores feminism in a way that could be beneficial to see. The viewer sees this in a strong and empowering way and also in extreme and harmful ways. Medea has both good and not so good examples of women's liberation. While Medea represents a strong genuinely fierce woman who is a force to be reckoned with. She comes across distant from other characters who she should be closer with; like other members of her family. Medea's passion and determination to achieve her goal I can imagine is refreshing to see when many female characters are portrayed as supporting and passive ones. Especially for a 1969 audience (which is the film I saw of the story), seeing a woman with that much drive and ability to excel probably felt invigorating. In fact, much of her character feels threatening almost to her counter male characters who don't see her for what she would like to be seen as. Unfortunately since most of the characters don't provide the "respect" she feels and frankly, we feel she might deserve, she's given less. Much less. I think this is where the story flips when this unfair misunderstanding makes things too unbearable for Medea. As she is tossed aside for another wife for Jason, she's seen as a tool or a means to an end and this is where I think, she takes it too far and removes herself from the title of "heroin."Her almost ruthless nature unravels when she kills her own children which is not only extreme but there is fundamentally something psychopathic when we imagine a mother killing her own child for selfish reasons. Arguably the most genuine and strongest bond we can imagine in human relationships is between a mother and her child. I think this is when her character changes in the viewer's eyes. We don't sympathize with her anymore and really question her sanity. She murdered her own children out of spite for her husband!I've wondered why Pasolini chose to write such a story and I think I have two theories: One, I think he might've been thinking about the innate power and determination women actually have. Perhaps it was a cautionary tale essentially saying "Don't mess with the women, they can actual tear you apart." Maybe he foresaw a time where women would strike back due to oppression and unequal treatment. My second theory is that maybe he's not very sympathetic to the female sex at all. Maybe he was attempting to suggest women will be the death of us if they are not "kept in check." Honestly I would like to think the first option but knowing Pasolini's other works and his seeming disregard for many good qualities of humanity in his films, I don't know how much I'd bet on it. Ultimately I wouldn't recommend it to examine female liberation but it is worth checking into for a discussion anyway.For film buffs, this one is checking out but maybe won't be the best example to examine closely. Technically and structurally there are moment-ruining flaws that are difficult to get over and with he exception of our lead, performances aren't extremely impressive. Definitely not for everyone.

chaos-rampant

I recommend this to any adventurous viewer, but on conditions.Viewers who generally favor the clean, painterly versions of myth will find this amateurish, too slow and too cryptic in its ritual. A few even seem to believe that the repetition of the murder of Glauce and Creon is there by an editing mistake, imagine! But that's how sloppy it seems.Viewers who want the cutting conflict of the original play, will also be disappointed. There is a bit of conventional Medea in the latter stages of the film, but most of it is filmed in hugely elliptical swathes, so the concrete despair and drama all but evaporate in the air.It is a marvelously flawed piece to be sure, an appealing quality to me; that is not the same as being sloppy as a result of ignorance, on the contrary it shows an openness to imperfection, adventure and discovery. And this is a film about all three in how we watch this myth, but in what way?Let's see. A significant point behind the exercise, revealed in the opening scene where the centaur lectures a young Jason on the purpose of myth, is that we have forgotten what is vital in the stories we tell, the rituals we enact. Scholarly talk of ritual dance or meditation is as removed from the purpose of either as can be, obvious enough. This is certainly true of so many Hollywood films (and Cinecitta of course), and not just of the mythical or quasi- historical variety. Oh they may excite within narrow limits of the action, but..So many are filmed in the same way as everything else, they do not transport us, which for me is a prerequisite of every film but particularly mythic narrative. The dresses and headgear change from the norm, but the world and drama conform to a trite familiarity of other films. Though it takes place in strange, different times, a film like Ben Hur is filmed as static affirmation of visual and narrative norms; never more apparent than in the scenes with Jesus, presenting the passions in a stagy, painterly way we associate as real because the same images have been repeated for so long—say, the Crucifixion. Even Scorsese fell foul of this in both his Jesus and Buddhist films.So instead of giving us a vital presence in that world that will awaken a direct curiosity to know, they make us a dull spectator from a safe distance. We duly admire the perfection of the art and platitude of the lessons, the exact opposite of the nature of that story in particular, and spiritual insight in general. We see the mundaneness of the sacred, and not the opposite which is the spiritual essence—if we can't see transience in the traffic of Saturday night party-goers and can only read it from a Zen book, we've wasted our time.It seems this was in part why Pasolini undertook his Gospel film in the first place, show a world we know from fixed images with a real gravity that will invigorate a sense of intense, spiritual curiosity—the storylessons were the same, what changed was the air around the story.This is carried here. The point is that myth (by extension: the narrative and cinematic ritual) can only matter, be truly ecstatic, when it is really 'real' (not the same as realistic), which is to say something can only be vital when it escapes the routine of mind, and becomes 'alive' in the moment of watching. This is at the heart of the philosophical mind problem: structure does not begin to account for experience.So this is what we have here. All the effort goes to loosening up our sense of 'realistic' routine reality; the music is a mixture of Buddhist throat chanting, Japanese shamisen, Amerindian ululation, African tribal drums; the dresses and gear a mixture of Slavic, Maghrebi, Greco-Roman origins. At this point, you'll either think of it nonsensical or begin your immersion beyond sense. The point is that this is a hazy world a little outside maps and time, undefined yet. But within this world, Pasolini creates an experience of intense 'being there'—in his camera, in his chosen places and fabrics, in the textures of light, it feels like we are present. Oh it is still an abstract ritual, but one that has sense, and that sense is carried entirely in the air of the film, not in any spoken conflict.Further within the ritual, we have Medea's own magical timeflow of conflicting urges and dreams, channeled by Callas channeling her own anxieties with fame and husband, inseparable from all else. Her presence is so intense, it may be creating imaginary madness in a key scene—this seems to be why we see the burning Glauce in the dream but not out of it. The bit with the centaur may be silly, but that is Pasolini telling us a bit about the film he's made. The rest is so, so wonderfully conceived. The opening with the boy touching the sacredness of nature in every small thing is like out of Malick, 25 years before. During this time, Pasolini was perhaps the only one (with Parajanov) who could rival Tarkovsky in his cinematic flow.

hasosch

The parable of the story of Medea is known: It is the hatred of a woman. Jason, son of King Aison, is searching the Golden Fleece by whose power he intends to push his uncle Pelias from the throne which he had gained unlawfully. When Jason arrives in Kolchis, he meets Medea who immediately falls in love with him and helps him to get the Golden Fleece. Returned to Jason's homeland, they get married. Medea gives birth to two children, but the end of happiness is already in sight. Because of ambition, Jason abandons his family in order to marry Glauke, the young daughter of the king of Korinthos. Medea, blind with jealousy, takes gruesome revenge. She kills her children, minces Jason's father and poisons Glauke's children.However, Pasolini would not be Pasolini if he would just film an ancient Greek myth that belongs since centuries to the common knowledge of any learned European. Pasolini himself wrote: "The film deals with the conflict between the old religion and the atheist modern world". As if he wanted to underline his breaking off the original parable, he substituted the Greek costumes by African ones. Africa was in Pasolini's focus at least since 1971, when he began shooting his documentary "Le mura di Sana'a". By changing not only the original meaning of the Medea-parable, but by transferring the area of the play to the black continent, Pasolini also gave as a further interpretation of the Medea-parable the abyss between the Third World and the colonialist West.

jaibo

Incredibly abstruse visualisation of the myth, allowing Pasolini to explore the conflict - a psychological and social conflict - between an older order of magic and the new order of reason and "civilisation". Jason needs Medea, repository of occult knowledge and superstitious practise, to help establish his rule; when he gets there, she is side-lined, and takes a terrible revenge. The storytelling here is oblique and elliptical, full of gorgeous images, sensual locations and sounds the like of which human ears rarely get to hear, full of ululations and Dionysian frenzy.The most intriguing segments involve Jason's relationship with his mentor, the centaur, who appeared in his childhood as a horse-man and his adulthood in normal human form, but the horse-form remains as a mythic trace once childhood is departed.The athlete Pasolini casts as Jason does well, physically scrumptious as he is and with the requisite banal arrogance; the casting of Maria Callas as Medea is more problematic - she's so obviously the product of the higher echelons of civilised culture that it is impossible to see her as a primitive force - her presence threatens to turn the film into a jaded millionairess' arty home movie. Still, if you try to ignore her patrician features and over-indulgent false-eyelashes, there's plenty of Pasolinian delights on display, and hardly anything in the film you would be able to see in anyone else's version of cinema.

AD

AD