LeonLouisRicci

Simply Put...The Title is a Reference to Marshall Mcluhan's Philosophical, Ground Breaking Book and Theory

"Understanding Media" (1964), and a Companion Piece "The Medium is the Message". Television, for Example is a "Cool" Medium and The Printed Word "Hot". Based on the Amount of "Thinking" or "Work" one has to put into the "Message" being Communicated, not to mention the Texture or Form used to Present it.This much Talked About, but Previously Rarely Seen (it is out now on Blu-ray from Criterion) Film was and is a Significant Piece of Art that Bridges the World of the Real and a Surreal World and Creates a Masterpiece of "Cinema-Verite" "Documenting" a Time and Place of such Cultural, Political, and National Zeitgeist that it is Really "Miraculous" that Cinematographer, and First Time Director, Haxell Wexler seems to have been "Blessed" for being in the Right Place at the Right Time.Choosing to Mix "Real Documentary Footage" and Dramatic Recreations of Real Events and Adding a Love Story about a TV Cameraman that is so Immersed in a Chaotic Collision of Gigantic Proportion, that He can not help but be Transformed, and Enlightened to just how much "The Whole World is Watching" what is taking place on the Streets and on TV Screens Everywhere.Robert Forster and Verna Bloom are Memorable and the Film Itself can not be Forgotten both Literally and Figuratively. It really is Art that is Important.Wexler also does not have the "Luxury" of Hindsight, Reflection, or History when He put together this Powerful Film as it was Released barely a Year after the Climactic Events of the Movie took Place.A Must See for Cultural and all Historians.

dougdoepke

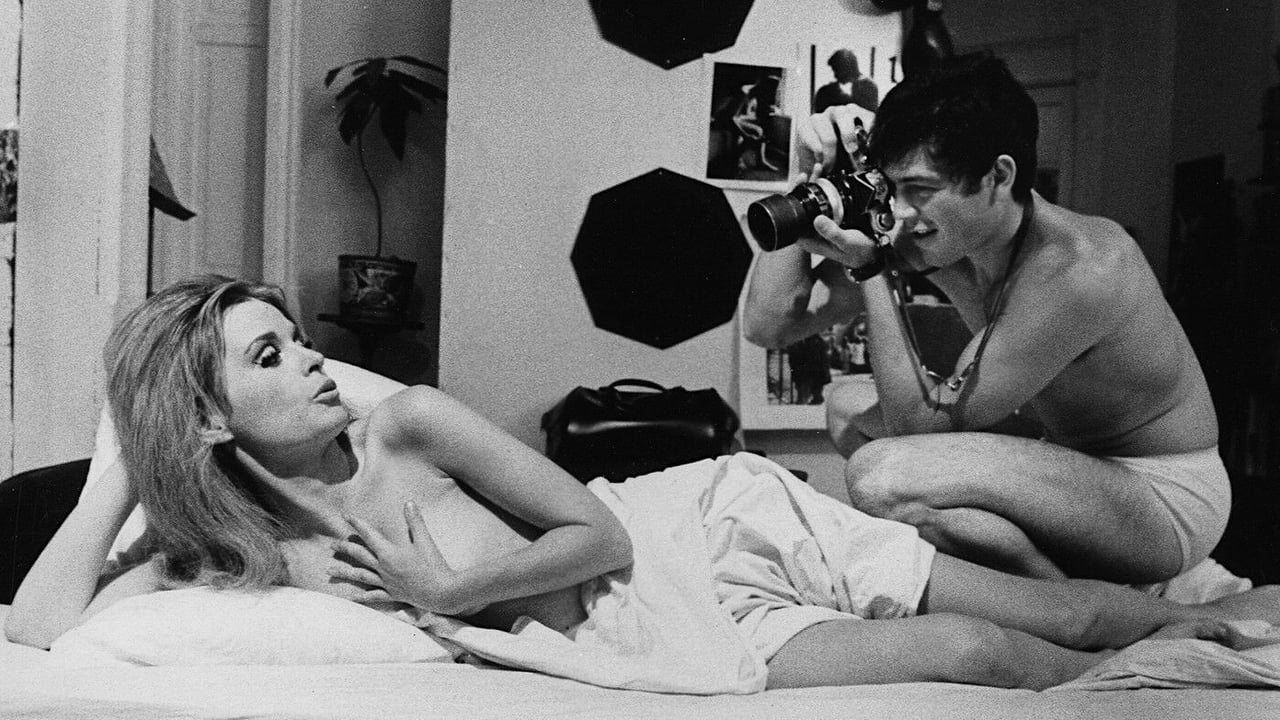

This unusual film combines fictional narrative with live footage of the turbulent 1968 Democratic convention.The movie made a splash upon first release. At the time, it couldn't have been more topical for the explosive political events then taking place. Director Wexler had his camera fortuitously placed to catch the bloody clash between protesters and Chicago cops backed up by the National Guard at the 1968 Democratic convention. Wexler caught the afternoon clash in the park, but not the probably unfilmable bloodier riot of that evening. Nonetheless, it's near documentary footage of an historic event that remains the movie's chief attraction.The movie itself is non-linear, with little narrative or dialogue. Instead it fades in and out on reporter Cassellis (Forster) as he learns some ugly truths about the state of the nation, circa- 1968. His and cameraman Gus's (Bonerz's) run-in with the black radicals in a Chicago ghetto remains a haunting slice of angry cinema and appears, to me at least, to be largely unscripted. I expect it was the first personal exposure many white audiences had to black rage then bubbling up in urban centers. This angry encounter, combining with raucous anti- war protesters and paramilitary police, present a vivid profile of the civil unrest of the time-- (Oddly, however, I don't believe the word 'Vietnam' is uttered once in the dialogue).We also get a sense of dislocation through the characters of Eileen (Bloom) and small son Harold (Blankenship). Uprooted from their West Virginia home by an absentee father, Eileen now ekes out a living in Chicago, while Harold tries to adjust to city ways. Their rural background and accents mark them as hillbillies in their new surroundings. Nonetheless, the sophisticated Cassellis finds Eileen's naïve simplicity appealing, and their little tour of the psychedelic nightclub reveals something of the urban counterculture flourishing at the time.I get the feeling Wexler wasn't sure how to end the quasi-narrative part of the movie, and there, I believe, he stumbles by settling for a clear contrivance. Nonetheless, the movie's last shot of his turning the camera onto us suggests we too are part of the story, which seems fitting for a film of this innovative sort. Anyway, the movie remains a one-of-a-kind, and though no longer topical, does furnish a fascinating glimpse of a turbulent time, which in many ways is still with us.

eschetic-2

9/11/2011 is probably the wrong time to be writing a review of this ground breaking film, but it was an almost perfect time to re-watch this evocation of some of the painful events of our college years.The "cinema verité" look of this film has taken on a somewhat dated feel with the years, and Robert Forster's intense stares have not gained in stature as examples of great acting - but both still accomplish what they did originally, wrapping us up in the emotions of a world gone slightly mad, being pulled apart by generations unable to agree on how best to defend freedoms both believed they believed in.The riots - youth and police - that marked the 1968 Chicago convention (following the other party's now generally forgotten charade in Miami) were the beginning of something we are only now beginning to recover from in this country. Then as now, a foreign civil war which part of the country felt it was in our interest to meddle in was tearing the country apart. (Meddling which proved mistaken in that case - misunderstanding how nationalism trumped a foolish "Domino Theory" and not helped by the failure of the media to adequately REPORT the ramifications and LEADERS of the independence movement which had transformed the former "French" Indochina into Vietnam in the 1950's, making the ultimate victors in the civil war all but inevitable). MEDIUM COOL was a somewhat disjointed but stirring attempt to come to grips with and hold a mirror up to a nation uncomfortable with seeing itself - let alone establishing a dialog across generational lines or dealing with the issues dividing it.Perhaps edgy popular entertainment was a hopeless tool to try to bridge that cap, especially without addressing the external causes driving the rift, but it was a start - and the artifact remains today a powerful glimpse back at what seemed like a world of irreconcilable political differences that may help us put some of today's stresses in perspective.One can only wish that rather than preserving two holes in the ground (no matter how "prettied up" by trees and benches) someone would genuinely memorialize the tragic events Americans have come to know as "9/11" by making a MEDIUM COOL-type film looking at the well meaning terrorists on both sides in the ten years since the Towers fell. That might be the best memorial - one people could actually learn from - to the thousands of people killed that day and in the wars and political upheaval which followed.

jzappa

One of the most truthful moments I've seen in a film in a long time: We hear MLK speaking on TV, a professional cameraman watching. We hear King's immortal words which have resounded through the decades, and when Forster finally speaks, he says, "God, I love shooting on film." Medium Cool is full of moments like this, where we see or hear something that plugs into what we're truly thinking, disconcertingly enough, at times when what we're thinking seems to obviously be something else. In Medium Cool, we respond to these things and, some forty years later, aren't quite sure what's real and what's not. This most head-on and seemingly makeshift of films was released in 1969 to reaction and surmise. Five years before, it would have been deemed unintelligible to the general movie audience. What happened, I suppose, is that by then we'd become so trained by the quick-cutting, idea suggestion and stream of consciousness of concepts in TV commercials that we process more quickly than feature-length movies can move. We get cinematic fast-sketch. And we like movies that recognize our intelligence.Traditional film narratives pronounce themselves: We know all the main techniques/content and archetypal characters. Haskell Wexler's Medium Cool is one of several movies of the late 1960s and '70s that's conscious of these things about movie audiences, like Seconds, Easy Rider, Mean Streets, Who's That Knocking At My Door, The Graduate, The French Connection, etc. Of the bunch, Medium Cool is probably the most visceral. That may be since Wexler, for most of his career, has been a cinematographer, and so he's conditioned to see a movie pertaining to what's being shown and not shown on-screen more than its dialogue and story.Wexler fabricates a fictional story about the TV cameraman, his passion, his profession, his girl and her son. There is also documentary footage about the riots during the Democratic convention. There is a chain of conscious scenarios that supposes reality (women taking marksmanship practice, the TV crew confronting black militants). There are fictitious characters in actual documentary scenes and vice versa. The misstep would be to segregate the real-life elements from the made-up. They're all equally meaningful. The National Guard troops are no more real than the love scene, or the artificial collision that ends the film. All the images have significance due to the way they are connected to each other.Wexler induces our recollection of the zillions of other movies we've seen to import things about his plot that he never elucidates on screen. The essential account of the romance (young professional falls in love with war-widow, eventually obtains companionship of her resentful son) is surely not innovative. If Wexler had formalized it, it would have been commonplace and dull. Rather, he specializes in the emblematic and important features of this histrionic (the boy likes pigeons, the woman is a teacher, the location is Uptown, the time is the Democratic convention, the woman feels more authentic to the cameraman than the model he's living with). And these are the scenes Wexler shoots. The leftovers of the relationship are implicit and never shown, eschewing the often essentially unnecessary 2 on our way from 1 to 3.And Medium Cool also sees not images but their purpose: Wexler doesn't see the hippie kids in Grant Park as hippie kids. He doesn't see the clothes or the folkways, and he doesn't hear the words. He distinguishes their purpose; they are there completely owing to the National Guard being there, and the opposite. Both sides have a purpose just when they encounter one another. Without the encounter, all you'd have would be the kids, dispersed all over the country, and the guardsmen, dressed in civilian clothes and spending the week on their daily grinds. That's interesting too, but it's not what they are that's significant in this film; it's what they're doing there.Medium Cool is ultimately so seminal, and engaging, owing to the way Wexler braids all these components together. He has made a nearly consummate model of the movie of its time. Since we are so conscious this is a movie, it feels more pertinent and authentic than the graceful fictitious artifice of most other films, including better ones. This befits the last scene all by itself, that chance event that occurs for no reason at all. Chance events are invariably chance events, not fate, not God's will, not karma, and they never occur for a greater purpose. When we get it, it hit me that it's the first movie collision I've ever seen that we weren't anticipating for five minutes before.

AD

AD