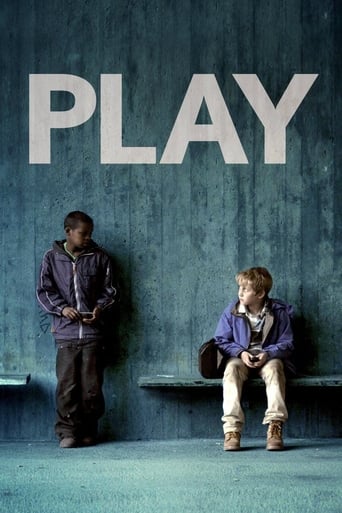

johnnyboyz

"Sweden!" cried out President Donald Trump some time ago. 'Just look at what has happened in Sweden!' he seemed to proclaim again. But what did he mean? "Play" is the title of a devilish Ruben Östlund film; a strange amalgamation of "La Haine" and "Funny Games" which combines cinema vérité with psychological horror and social commentary. What social commentary, it seems, is left up to the viewer: audiences have appeared to whittle it down to one of two (but it could be both) things: class and ethnicity, with Swedish politicians even finding time to chip in to make thoughts known - do remarks by socialists expunge the film from charges of racism when they proclaim it is about class? Or is "Play" so clever, that they have entirely missed the fact it is a damning critic of multiculturalism.The film opens in a shopping centre with a disagreement between two Swedish boys over an amount of money one of them has dropped and lost. "500 Krona!?" one of them exclaims - 'it's nothing', replies the other. Across the way, however, a gang of black youths who are mostly their age are eyeing them up in order to essentially mug them. Within the first scene, Östlund wants us to realise this is a society characterised by differences in income and racial disparity.Elsewhere in the film is the lament that authority has disappeared from Swedish society: bus conductors; mall security guards and shop assistants are either powerless to giving louts a good whack or vacant altogether, save for nearer the very end where they exasperatingly appear at just the wrong moment to punish the wrong people. The film enjoys its static camera-work and neo-realistic settings, wherein dozens of people wander around the public domain, but what seems to have been deliberately kept of screen above all else is the presence of a policeman. Where this seems to lead, or will eventually lead, is an increase in vigilantism - parents and friends of those already victim to spates of crime taking matters into their own hands and administering their own forms of justice in the absence of a state enforcing the law: not unlike various London communities forced into defending themselves form the hordes in 2011, or other groups trying to do something about paedophile gangs operating under the radar in northern England. There are two instances of this in "Play", one closing the film which doubly encompasses Sweden's apparent ignorance to what is going on amongst its young that someone is labelled a racist for trying to obtain justice. "Play" depicts a couple of hours in the life of three boys in the city of Gothenburg and its outskirts on a grey winter's day - they are Sebastian; Alex and John, although John is of Chinese ethnicity. Whatever the problem with immigration, or immigrant crime waves specifically, John has at least seemingly integrated. When we first encounter them, they are at the offices where one of their mothers works - an upscale law firm (we can read "Adact" on the wall) whose employees dress impeccably. Östlund loiters on the entrance of the office for a while after everyone has departed, almost pointlessly, until a staffer reveals the practice to be so bourgeois that they wipe clean a glass door that was already in perfect condition. Sebastian et al. traverse to the local shopping mall, where the earlier group of black youths are still messing around having failed to lull the twosome from the opening scene into what will transpire to be a psychologically sadistic game of bullying and robbery. The two groups first come into contact in a sports shop, where Östlund quite brilliantly keeps the coloured gang off-screen as they holler and whoop while we focus on our increasingly anxious protagonists. By the time they have been followed outside and onto the tram home, it is evident something is wrong, and from there transpires the rest of the harrowing tale.The film's beating heart, the idea that bullies belonging to a minority string defenceless white Swedish kids along to mug them, I read is based on a spate of actual incidences of this happening over a three year period. Meanwhile, adults are too ditzy worrying about broken porcelain in cafes and blocked aisles on trains to really notice what's going on. Writers and journalists such as Jonas Hassen-Khemiri and Åsa Linderborg have made accusations, veiled or otherwise, that the film is in some way racist, while America Zavala applauds it for attacking the pitfalls of a system characterised by class. Thematically, the film seems to reach the conclusion that Sweden is a racially and culturally diverse place - whites don dreadlocks and listen to reggae; Native Americans busk in town squares and white girls dance to Zimbabwean pop music for school performance projects. It is, however, experiencing teething problems as it makes some sort of cordial transition into multicultural permanency. When all is said and done, one does not have to do much research to find stories, radiating in particular out of the city of Malmo, which report chaos and a complete social breakdown on account of multi-racial ghettos rioting for reasons that even the police do not know. One may also read of 'no-go' zones and youth criminality in classrooms so rife that schools have even had to shut for periods of time due to teachers feeling unsafe. Whatever the answer to any of this, Östlund has above all other things managed to make something which actually feels like a piece of cinema - something free of convention; something unpredictable and both harrowing and atmospheric without any real need for pyrotechnics. It is wholly worth seeing for these reasons and more.

lioil

A visually interesting and unusual movie. It is centered around rather a chilling story of bullying that is built very slowly thus making it thrilling and terrifying, since we are conditioned to expect some bloody climax; yet the horror happens only in the subtle way of exposing the violence which is in conforming. The main story is cut several times by visuals of a parallel yet empty story that pretends to add to meaning. Again both stories are expected {we are conditioned to expect} to join in some great climax yet it does happen just in quite a meaningless way. The movie is full of visual fluff that is there to amplify any interpretation one can see. Some parts are missing, again to punish expectations. Like when the boy gets to the treetop and an interesting discussion develops. All is cut: somehow he is back down, yet why? To conform with his comrades who had let him down before? Conforming or conditioning that makes people insensitive to what is and so react predictably is also exposed in reactions of shopkeeper, passengers, disturbed ladies at the end. Street-smarts count on predictability of petty minds; bullying may continue. Should have been shorter.

juoj8

The film shows a group of bullies and their relationship with their victims, and how the group works during different circumstances. The movie is based on actual events in Gothenburg, where kids used a scheme wherein they accused their targets of having stolen mobile phones. Through coercion and psychological violence they then make the victims to hand over the cell phone to get out of the uncomfortable situation that arises. During the movie, the power relationship between the groups, the bullies and the victims, often changes and the bullies ask their victims for help, which they also get, as the victims play along in the social setup that has been created. The interactions with adults that the groups have are unsettling. The adults often refuse to interfere, perhaps due to insecurity about where the line goes, or whether they are assumed to interfere. Some adults also seem to downplay what is happening in front of them, almost acting as if children cannot abuse other children, and what they witness is child's play.Ultimately, the adults and the children seem to be from different worlds altogether, worlds that are not meant to meet.The end has several interesting twists. One of them is when, several months later, one parent of the robbed children finds one of the perpetrators, and decides to confront him. This is done in a similar bully-like way as the bullies were using in the first place. During the movie I felt very angry and upset, and I was picturing several ways I would deal with the bullies. But this last scene shows the futility of acting in such short-sighted ways; the reasons for acting like bullies are reinforced as he views himself even more of an outsider, and the abusive parents are later confronted by onlookers.Trying to explain their frustration and the situation to the confronting onlookers, I feel as if the parents are not only talking for themselves, but also for my own viewpoints.The absurdity of using bullying to stop bullying is exposed, and I laugh at my own simple and reductionist reactions I had just a few minutes ago. This was an great movie, one of the best, most developed depictions of human behavior, domination and submission in social interaction. If I ever become a parent, I would definitely show this movie to my children as they are about to enter school, to discuss how to deal with bullies and to talk about how bullying arises.

Howard Schumann

Based on an actual racial incident in Gothenburg, Sweden in which a group of black teenagers carried out a series of thefts of other children's personal belongings for a period of two years, Swedish director Ruben Ostlund's Play is about using psychological game playing rather than name-calling, threats, or overt violence to bully your target. It is a compelling study of how our lives are often run by stereotypes, racial or otherwise, and how the line between victims and victimizers can be a thin one. In this case, both the bullies and the victims are children, but the games people play could just as easily apply to adults, or even governments.One of the most promising young filmmakers, whose style is reminiscent of Michael Haneke and Roy Andersson, Ostlund's camera is observational, simply recording what is taking place without comment. The film opens inside a shopping mall where we see a panoramic view that includes the shops, stairways, and two levels, highlighting even the smallest detail. We hear the sound of conversations but do not know where they are coming from. The camera then zooms in on two small white middle-class children walking through the mall lobby. They are approached from the left by five 12-14 year-old boys (all black and immigrants) who ask them for the correct time.The game is established early, though the main victims of the film are three other children of well-to-do parents who appear later. Most likely repeated many, many times during their two-year crime spree, the game is played like this. One of the approaching black teens asks a younger child for the time. When the white child pulls out his cell phone to check the time, he is accused of stealing the phone that belongs to his alleged brother. He tells the boy that the phone has the same exact scratch on it as the one that was stolen from his brother, and asks to confirm it by showing it to his brother.When the child refuses, a "good cop/bad cop" routine is played out in which one of the five pretends to be a friend of the harassed boy. The child inevitably denies that he stole the phone giving the "good cop" the job of reassuring him, saying, "Okay, I believe you, but we have to solve this, right?" He tells the boy not to worry, that his friends are not trying to rob or hurt them. At the same time, the "bad cops" are making aggressive demands in an intimidating manner. Ostlund keeps the characters at a distance with mostly long static shots, yet we feel that we are there with the victims, acutely feeling their tension, frustration, and growing fear.The scenario is then repeated, this time with three other children, two white (Sebastian and Alex and John who is of Asian origin). Compelled by fear and insecurity, the boys allow the bullies to control the game and only rarely ask for support from adults. When they do come in contact with them, the adults are reluctant to become involved, or, as shown later in the film, become involved inappropriately. The white boys are forced to follow their black tormentors around the city, on trams, and buses, then finally out into a remote, wooded area of Gothenburg where the game is played until its ultimate end point. Though the victims have several opportunities to escape, they do not take them, perhaps because the fear of black violence has been so firmly instilled in them that they feel that they have to be "nice" in order to save themselves.Play has a light touch as well. In one scene, a group of feather-clad Indians do a war chant for donations in the middle of a busy street. In another amusing sequence, a cradle is placed between the second and third compartments on a moving train and remains there despite the urgent pleas of the conductor to move it for safety reasons. When he gets no response in Swedish, he repeats the warning in English. One of the key moments of the film is a sudden attack by older gang members against the young perpetrators in the back of a bus. Later, when one of the gang of thieves wants out, he is kicked and beaten inside the bus by the other four. Also, in a reversal of roles, the bullies blame the bullied. One says, "Anyone dumb enough to show his cell phone to five black guys deserves whatever he gets." Finally, an end game is set up by the perpetrators. A contest takes place in which both sides choose their fastest runners and whoever wins the race gets to take everyone's valuables. Of course, the winner is pre-determined and the white children lose all of their personal belongings, including their cell phones, a jacket, and an expensive clarinet belonging to John. A follow-up to Ostlund's highly praised 2008 film, Involuntary, Play is a complex and multi-layered film that has a surprise twist near the end. Filled with sharp insights into human behavior, Ostlund challenges us to shine a mirror on our own behavior and see whether or not we employ the same kind of psychological tricks ourselves to get what we want. Despite an ugly moment that does not add anything to the film, Play is a brilliant work of art that deserves to be seen.

AD

AD