Horst in Translation (filmreviews@web.de)

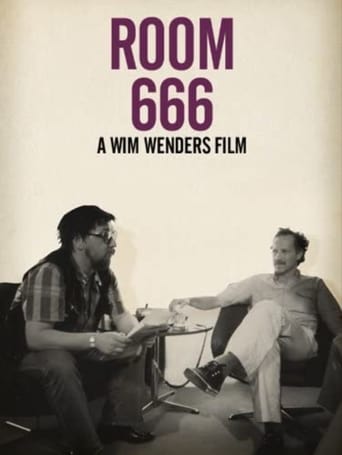

"Chambre 666" or "Room 666" is a 45-minute documentary movie from 1982, which will have its 35th anniversary next year. The director is Wim Wenders and he made this fairly short film at the Cannes Film Festival. He used the fact that several fairly famous filmmakers were present and managed to get them into a room one-by-one. On a note they read a question, namely what they think about the future of cinema and how things will develop in the next years/decades. Wenders also can be seen briefly near the end when he introduces a Turkish filmmaker who could not be present, but has submitted an audio message. I liked quite a lot how Wenders left the screen after showing us a photo of the man talking. I don't want to say all the filmmakers you see in here, you can check it for yourself in the list here on IMDb, but it's all about what they say and how they say it. Some sit down all the time, some keep moving, everybody has their way of telling us his thoughts. Some talk very briefly (like Fassbinder who died not much later), some talk a whole lot (like Godard early on). Wenders included filmmakers from all kinds of countries and also women filmmakers. This is certainly an interesting watch to see how people saw the medium of film and how they thought it would progress. I do think sometimes it is too specific though for general audiences, but aspiring filmmakers or people who study in the art of filmmaking should really check it out. I enjoyed the watch for sure. Very simple premise, very effective outcome. Make sure you get subtitles as all the filmmakers speak in their respective language.

tieman64

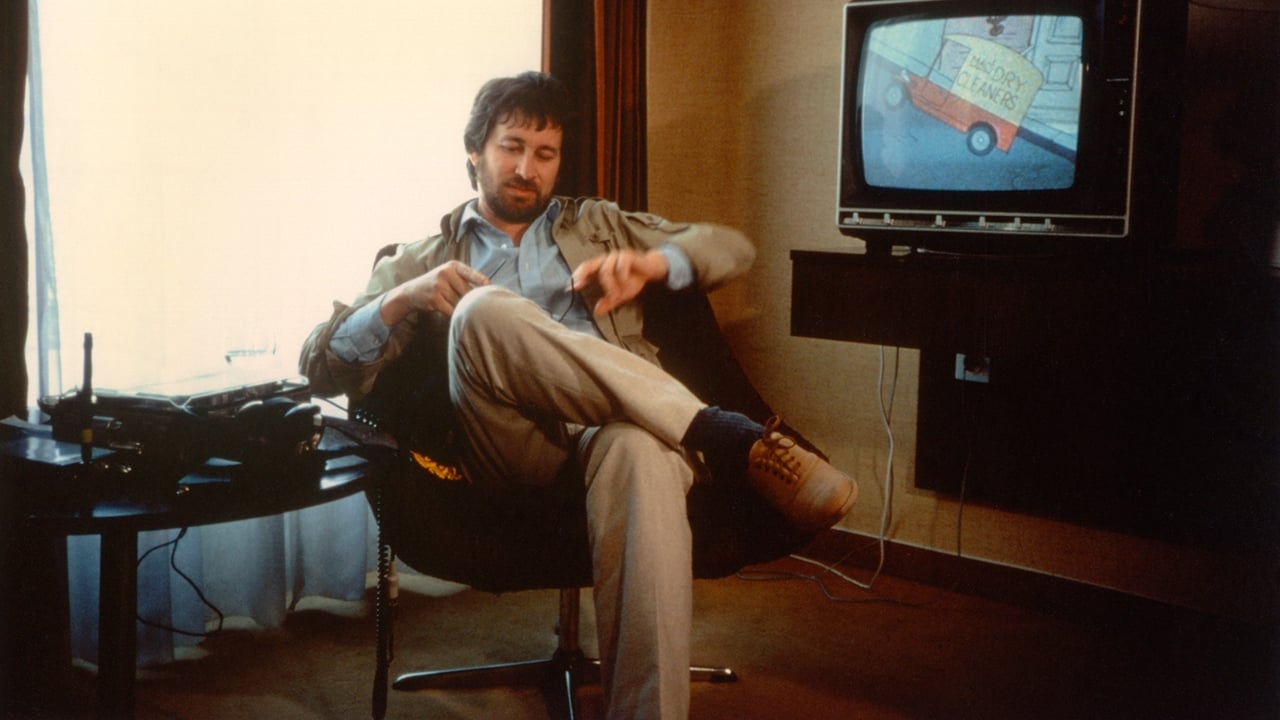

During the 1982 Cannes Film Festival, director Wim Wenders invited several attending filmmakers to participate in a small experiment. He prepared a sparse hotel room, placed an unmanned camera and tape recorder in opposing corners, and urged each filmmaker to respond to a prepared list of questions whilst alone and unattended.Cunningly, Wenders positions a camera, television and a chair such that each interviewed film-maker is forced to turn his back to a television set. As the film unfolds, questions of new media's effects on cinema are discussed, as well as cinema's ability to generate affect in the wake of various technological advancements. The television behind the film-makers thus becomes both a threat and a challenge; a generation of artists faced with the menace of new media looming over their shoulders, as well as goaded into turning around and directly facing a new enemy at worst, paradigm at best."Room 666" captures the moment when a certain brand of cinema died, that moment after the 70s when Hollywood's power structures were rebuilt, blockbusters and the all-important opening weekend became king, less projects were green lit, creativity was strangled, special effects became the raison d'etre of most films, blanket global releases, infantilism and set-piece cinema became the norm, and narratives increasingly took the form of amusement park rides.Moreover, the film captures that moment when artists like Antonioni, Godard, Bergman, Altman, Fassbinder and company were pushed aside. In an instant they became the old guard, unwanted in this new world, each now finding it hard to get distribution, let alone funding. Fittingly, Fassbinder looks a mess, tired and dejected. He'd commit suicide soon after.The film features a number of film-makers, some more interesting than others. Godard, unsurprisingly, gives the longest rant. He's dismissive of television, but accepts that it and new technologies will increasingly stifle cinema, just as cinema killed theatre and the novel. Small films will disappear, he predicts, before likening globalisation and the disappearance of small nations to the homogenization of cinema. For Godard, Hollywood commodifies everything, reappropriates all culture.Bizarrely Godard then starts asking why people have kids, before making some valid points about postmodernism: "more and more movies talk only about movies, rather than a reality outside the cinema," he says, before pointing out how this self-reference (what he calls text) serves, ironically, only to distract audiences from the similarities between each rehash. And these stories are always comforting, he says, reassuring fantasies, repeatedly redressed and resold.Werner Herzog appears too. Hilariously, he dismissively turns off the television behind him, and then takes off his socks and shoes ("These are not questions that can be answered with shoes on"). Fellow German Rainer Fassbinder pops up as well, both Germans talking about the rise of spectacle cinema. Herzog makes an interesting point about TV being mobile while cinema is fixed, authoritative. Today the opposite is somewhat true, TV going through a golden age while cinema suffers a massive identity crisis, unable to keep up with the possibilities of television, the internet and video games, the former now a writer's medium, offering extended, overarching narratives, the latter providing a interactive buzz which cinema can't compete with. Indeed, what's most ironic about "Room 666" is that most of these film-makers attribute the degeneration of cinema to the rise of empty spectacle (George Lucas, Steven Spielberg and company), whilst today cinema suffers a death of spectacle, and all content of substance has moved to TV and the net. With all these changes you then get a certain accelerated perishability. It is not only that the subject/object dichotomy between audience and art is now destroyed, but that the very authority and permanence of art as an object is diluted, material created, consumed and discarded in an instant (which gives rise to various forms of elitism).Noel Simsolo and Monte Hellman pop up next, both moaning about a rise in stupid movies. Hellman says he is addicted to taping movies and not watching them, an addiction which many suffer in our internet age, downloading so much digital pleasure that consuming it all becomes a chore. The super ego's demand that you "enjoy" has become a curse.Filipino director Mike de Leon shows up, but then quickly leaves. Susan Seidelman spouts some half baked wisdom about movies being driven by passion, but Mahroun Bagdadi wisely undermines her. It is the love for movies that has disconnected filmmakers from real life experiences, he points out, the "brat pack" generation putting not real life on screen, but a version they've learnt from the movies of others. Van Gogh made a similar point about paintings centuries ago.Pretentiously, Ana Carolina states that no true artist would be interested in working with the electronic image anyway. Turkish director Yilmaz Güney, who at the time was facing extradition, agrees that independence and the artist's vision is steadily being crushed by the logic of capitalism. In Turkey, he says, progressive cinema "is constantly being suppressed, banned, punished, silenced, by some dominant forces." Michaelangelo Antonioni turns out to be the most prophetic, foreseeing a time when films are watched in the home on large screens from a high definition source. He then talks about the possible effects of video, none of which came to pass, of course, but are nevertheless applicable to our internet generation.And then there's Spielberg, the reason the film is titled "Room 666". Spielberg's the devil in the room, the guy possessing a slick cockiness which most of the other film-makers lack. Wenders would get increasingly critical of Spielberg as his career progressed, but here he keeps his distance, letting Spielberg condemn himself with his naivety and congenital disavowal. Always in denial, Spielberg calls himself an optimist. As he speaks, politicians rattle over his shoulder.8.9/10 – Worth one viewing. Similar fare: Cronenberg's "Camera" and "The Last Cinema in the World".

MisterWhiplash

Wim Wenders was curious at the 1982 Cannes Film Festival about the future of cinema. At the time it was at the end, or just a change, in a time in film-making when it seemed like anything was possible. The 1970's saw New-Waves in America and Germany, plus some original talent from France (Akerman), Italy (Bertolucci and Wertmuller), and elsewhere, but by 1982 things seemed a little bleak, apparently. Commercialism was rising high, and Steven Spielberg's friend George Lucas was unintentionally leading the charge to a more Blockbuster-oriented cinema worldwide, relegating art to the 'art-houses'. So, Wenders brought in a bunch of filmmakers to talk, right to the camera, on their thoughts about the future in film, if there was one, what about TV, etc.We get two extremes of thought and response, actually, between two icons of cinema for different reasons: Jean-Luc Godard and Steven Spielberg. While Godard keeps looking at the letter, giving one an odd impression (he's the first interview) that he's just reading from the text and going on in messages that, yeah, film is screwed but it still is different from TV, Spielberg is more optimistic but cautious in making sure to take into account the finance of film, the figures. In-between these two figures, one an obtuse intellectual and the other a classic showman, we get a variety of thoughts and takes, some more pessimistic then others. One of the best interviews comes from Werner Herzog, who decides he must take off his shoes and socks before the interview because of the depth of the question (he also turns off the TV in the room, which no one else does).Sadly, we also see some of the decline right in the room. One of the titans of cinema from the 'New-Wave' period, Michelangelo Antonioni, thinks cinema can evolve but that it will probably die at some point because of new mediums like video (oh if he only knew). And another, Fassbinder, looks tired and bloated, giving a half-assed if interesting answer (he would die a couple of months later). Some others give a dour impression, like Paul Morrissey, but it's not altogether unhopeful words said. In fact what it amounts to, for Wenders, is a realistic assessment of cinema as it would progress in the 1980's and beyond: artists would have to be careful, or just be put into more constricting circumstances, as the medium expands and it changes the way people see movies.

Michael_Elliott

Chambre 666 (1982) *** (out of 4) Wim Winders directed this somewhat interesting documentary filmed during the 1982 Cannes Fil Festival. Winders set up a camera in a hotel room and he'd ask various directors to come in and say what they thought about the future of cinema. Werner Herzog, Steven Spielberg, Michelangelo Antonioni, Jean-Luc Godard, Paul Morrissey and various others take part and offer their thoughts on the subject. The opinions very from Herzog not fearing the future to Spielberg showing high concern over the budgets of big movies, which are forcing studios to cut back on smaller films. It's funny because he speaks of being worried about the $10 million it took to film E.T., which he says could cost $18 million in a few years. It's also interesting to hear Herzog "predict" that one day you might be able to order movies through a computer or television. There's nothing technically good about this 45-minute film but it's interesting none the less.

AD

AD