S M Aminul Islam

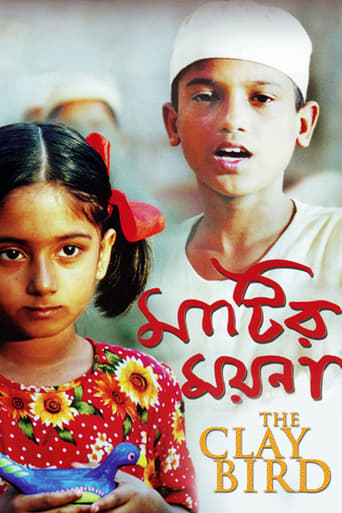

The film "The Clay Bird", also known as "Matir Moina", has brought about a groundbreaking development in the Bengal film industry while there was a very few films to be proud of as a Bangladeshi audience. It is the story about a child named Anu and his journey through different dimensions. Being brought up in a protective family, Anu was sent to a boarding religious school, locally known as a Madrasah. There he got to experience new things and meet new kids and people from diverse background. Anu finds Rokon, fellow student and a kid with weird behavior, as a trustworthy friend. Simultaneously, Anu's family has been going through various challenges battling against the superstitions of Anu's father who is so possessive about his beliefs and decisions. The film also pictured the political dilemma and controversy in people during the liberation war of Bangladesh in 1971.

rizwaanulhuq

The Clay Bird is a genuine story of its kind, full of warmth and charm, of exquisite symbolism, of ripping tensions of politics, adeptly told by Late Tareq Masud, a rave combination of content and craft from the cinematic landscape of Bangladesh. It's one of the finest films Bangladesh has ever produced with credited picturesque cinematography and technical soundness. Winner of a Cannes accolade and the first-ever official entry of Bangladesh to Academy Awards (in 2002), it deserves an engaging watch as it offers you more than what it contains on its gritty surface of celluloid. Placed in the time line of liberation war of Bangladesh, the movie begins with the idyllic life a common, everyday family in a village in Bangladesh. Anu, the juvenile protagonist, goes through the turbulent time of transformation taking place in the political scenario of the then East Pakistan and the coming crises of liberation war. The director offers you a look into the reality through the eye of a juvenile who wants to make sense of things at odds. The best part of the movie is its symbolism, projections of materials and scenes, which parallel a bunch of deeper meanings. The clay bird itself is a symbol of a Sufi treat, the urge to get emancipation from the earthly desires, the urge of liberation of human soul from earthly vessel of clay to the divine. The Sufi connotations are also present in the songs, such as: 'Pakhita Bondy ache deher khachay' ('The bird is caged in the shackles of body'). The girl sings the song in folk song battle. The clay bird does also symbolize the urge of making religion sane, making it proper and free, more human, more divine, more realistic than only the shackles of laws and regulations, rigid conducts and senseless allegiance. It also signifies the tension of society to accommodate the contesting rivals, aesthetics and belief.This is symbolically true representation of the then clergy over the mass, the tendency of controlling the every business even just a trivial toy of a child. In metaphysical level, the bird also symbolizes the society, which is judged, controlled, and authored by the superior forces often without the sensibility to its human nature. In this movie, Masud places songs trickily, in to the contexts, suggesting deeper aesthetic meanings, manifesting the ironies, or scratching questions to the intellect of audience's mind. Most of the songs are rare collection of folk songs, traditional baul songs (songs practiced by the homeless saints) or puthi (a kind of recitation of poetry with proper pace depicting the stories, sometimes religious issues, such as, the fatal battle of Karbala or Abraham's sacrifice of Ishmael (as Muslims believe). Bauls are secular in nature and the song sides with the common, grounded perspective, the true secular nature of common people of Bangladesh. The puthi (recitation of poetry) manifests a tension of father's choice and mother's dilemma, the matriarchal nature of Bengali society is echoed through Bibi Hazera's (Hager, mother of Ishmael) concern over her son rather than the patriarchal chivalry of first son's sacrifice to God. The song about Ali and Fatema is interesting too as we see the song glorifying the spiritual greatness of Prophet Muhammad's (PBUH) daughter Fatima (pbuh) over her husband Ali (pbuh). We see an elderly woman is rubbing the red vermilion off her head. Red vermilion is symbol of marriage to Hindu woman and the elderly woman is doing in fear of Pakistani occupational army lest the girls not be raped. The song ends with this scene connoting the complete contrast of celebrity of femininity and its disrespect. The movie paints an authentic tension of a society in search of its identity and political allegiance. Anu's father, Kazi Saheb, as an example, is a pro- Pakistan, pro-Islam person who believes in the unity of Pakistan. In contrast, we find Anu's young uncle, Milon, engaged in talk of Marxism, a pro- progressive guy who hopes high for liberation from autocratic rule of Pakistani militia. In the same family, two generations are in odds with their views. The Boatman's perspectives are also sarcastic, a bit pragmatic, and down-to-earth. His conversation to Anu's uncle, Milon, is quite true in the context of present Bangladesh. Indeed, the country is free from Pakistan in 71, but the political freedom of common man is still a far away thing. Anu's friend's illness is quite interesting. First Maulovi (Boro Huzur) thinks he is possessed by Jinns (demons) and treated in a voodoo manner. His illness parallels with the condition of the country and how it is mistreated. Anu's sister, Asma, also dies. She has been treated with homeopathic medicine (a common trend back then). Anu's father, Kazi Saheb, fails to cure her and she dies. His rigidity ends up with a fatal blow, death of his daughter, with an awakened realization of the reality of failure of his faith over old ways. He may be honest and simple but fails to feel the pulse of an ailing society with crisis he has never met before, someone caught into the vicious cycle of stagnation, of rigidity of faith, of endless loop of old solutions to coming crises. Masud, intelligently, places himself as an observer, someone who is bringing a slice of 70's Bangladesh, how it looked back then, how people have gone through the formation of essential elements of coming liberation, the ripping tension between the old and new. As if, what he offers is nothing but the truth, and only truth reported from a perspective of a man, a boy or an entity which is trying to figure out the world at odds without judging what is good or bad, innocent or evil. It offers a nice representation of rural Bangladesh back then in '71 with every authenticity you can imagine, a piece of art devoid of chauvinistic chivalry of patriotism or melodrama of social romance.

Mohammad Raisul Russel

The real objective of the film, it seems, is to depict the ignorance and misunderstanding about the real cause of the struggle for freedom in then-East Pakistan, just before war of liberation. The film is about the mentality of the Bengali Muslims and their feeling about Pakistan, which largely arises from their apprehensions about the fate of Islam in the new country (i.e., Bangladesh). For many at the time, it was difficult to separate Islam from Pakistan, and so the rise of a new nation seemed to be a threat to Islam. However, the film sometimes establishes Islam and clerics as the source of evil and violence, as blind faith seems to be equated with social injustice. At the end of the film, one character says, "your Muslim brothers have killed them," a phrase that may sum up some of the objectives of the filmmaker. The depiction of some Muslims as ignorant may even be a ploy on the filmmaker's part to make the "other" acceptable to Western viewers. Nonetheless, several viewpoints are depicted, and Islam is seen in a broad, critical light.One of the best Bangladeshi movie I have ever seen.

Muldwych

"The bird's trapped in the body's cage. Its feet bound by worldly chains, it tries to fly but fails." 'The Clay Bird' opens a door into Bangladesh's fight for independence in the late 1960s when the soon-to-be nation state was a far-flung region of Pakistan, following the partitioning of India in 1947. Increasingly disenchanted with the distant central government due to racial, cultural and economic discrimination, Bangladeshis began taking to the streets in protest, demanding a general election as the springboard for autonomous rule. The election was cancelled and the Pakistani military were sent in to quell the uprising, murdering thousands and destroying population centres. A civil war ensued, eventually leading to independence in 1971. The film is set just prior to the prolonged and bloody uprising, as citizens find themselves galvanized along religious and political lines, with tempers beginning to fray. Rather than depict events at the heart of the capital, the story centres around the lives of a rural family in a remote village, bearing witness to the way in which the winds of change blew across the ordinary citizen. While the intent of this is sound, the end result is something of a mixed bag.The plight of the family proves an effective allegory for the various Bangladeshi attitudes to the turmoil their world is in. Kazi, the father, a born-again Muslim, reflects the ultra-conservative stand that faith and discipline will unite the people under Allah, and is unable or unwilling to accept that the deeply fractured society around him faces problems that cannot be solved through prayer. Milon, his brother, a young political extremist, stands ready to fight for the nation with the unwavering confidence of the just. Ayesha, Kazi's apolitical wife meanwhile, is interested simply in getting through the ordinary day to day struggles of life. Asma, the daughter, is too young to be constrained by the petty concerns of adults, while Anu, the young son, is propelled unwillingly by conflicting forces and ideologies he doesn't understand. It is the nation in miniature, about to burst at the seams.Yet there is a somewhat meandering quality to the pacing, perhaps in part because the writer has not entirely decided upon the story he wants to tell. It could very easily simply be the story of a young boy forced to attend a madrasa (Islamic boarding school) by a father terrified his son's mind will be polluted by non-Islamic ideas and therein be a commentary on Islamic extremism itself. Indeed, a large chunk of the film is just that: there is a very telling scene where the young Anu and his uncle watch a Hindu boat race, clearly enjoying themselves, only to be reprimanded for celebrating diversity. Kazi's religious fervour has him at odds with the rest of his family, incapable of being the father and husband they so desperately need. The dogma strangles the family to the point of dysfunction. Equally telling is the character of Milon, whose more secular and open-minded world view is the foundation for the forthcoming nation-state. Religious dogma is equated with denial, while the activist is the realist.Fortunately, the Islamic discourse eventually digs deeper and there is a nice scene where two of the madrasa teachers make the point that the religion spread so successfully across Bangladesh precisely because it was a peaceful ideology. Whatever one's beliefs, there can be no denying that this sort of discourse on Islam is rarely found outside of Islamic countries. The very idea that it must be spread by force and violence is just such a question pondered with dismay by one teacher struggling to understand how religion became part of the rising civil war in the first place. That the Muslim extremists involved in acts of terrorism rivaling the invading Pakistani army might be missing the point is one of the many tragedies of that war, though it is important to remember that many factors came into play, not least cultural and economic destitution. However, director Tarique Masud does not adequately explore these factors, which if the aim is to give a snapshot of society during that time is quite remiss, suggesting that he is more interested on religious commentary. Yet the film goes beyond the madrasa, so that those set up as the main characters then disappear for long stretches like the inhabitants of a Tolkien novel. This unravels the sequences designed to build up character story lines, with the disjointed result leading to the uneven pacing. This leaves the conflicts faced by some to be either insufficiently built up or not satisfyingly followed through. Masud ultimately needed to choose one storyline and stay with it.Nonetheless, the cast perform with the conviction and skill necessary to draw the viewer into their characters' worlds – when we are able. However, standouts for me include Russell Farazi as Rokon, Anu's one true friend at the madrasa - a likable, yet misunderstood loner, and the young Farazi is more than able to imbue the character with the complexities that reside in such a part. Soaeb Islam, meanwhile, brings to the wannabe revolutionary a warmth often without any dialogue whatsoever. And while Kazi, the stiff-necked Islamic convert, gives Jayanto Chattopadhyay not a lot of range, this does allow for a meaningful scene at the end where the horrors of war force the character to face his religious convictions. And while Nurul Islam Bablu is no Marina Golhabari, he gives Anu the profound innocence that the script requires of the character.Ultimately, 'The Clay Bird' is not quite the tale of Bengali struggle it purports to be, due to unfortunate scripting and editing choices that take much of the wind out of its sails as a result. However, it opened up a window into a history with which I was hitherto unfamiliar, with many thought-provoking and sometimes touching sequences that still manage to shine through – even if the sum of the parts is conspicuous by its absence.

AD

AD