maria m

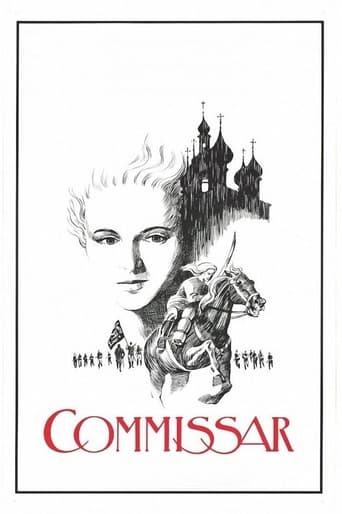

Commissar directed by Aleksandr Askoldov is a 1967 Soviet film based on one of Vasily Grossman's short stories. The story is set during the Russian Civil War and centers around a female commissar of the Red Army cavalry, Vavilova, who is introduced to the audience as a brutal soldier shooting a deserter with zero remorse. The audience clearly sees her inhumane nature when she finds herself pregnant and mentions how she would have gotten rid of "it" if only she had known earlier. Finding herself pregnant and due to deliver her baby any day she is forced to stay with a not so well off Jewish family who is at the beginning is reluctant to accept her staying with them. Through her time with this family her character makes a drastic change as she now embraces motherhood, and life as a woman. One of the many themes in this film is the effect war has had on adults and children alike. The husband, who is exhausted from constantly working while earning very little, but has to feed seven children. The wife, who has to do all the house chores. In one scene the children aggressively bully and begin to wage a mock pogrom on their older sister by tying her to a swing and swaying her back and forth. The action could have only been possible by observing the actions of soldiers. Although the family is caught in all this chaos Askoldov manages to capture the warm nature of family life through the slow panning of the children and their parents sleeping as well as them dancing together. Askoldov finds ways to dramatize particular scenes; one noticeable moment is the scene of Vavilova struggling during her delivery, which is paralleled with a scene of a group of soldiers struggling to push a wagon. Also the scene where the soldiers are drinking water after succeeding to push the wagon and the scene where Vavilova drinks water when she succeeds in giving birth. This film did not adhere to the honorable vision of Soviet life in war along with the aftermath that the party officials desired the world to see. The audience is made aware of the Soviet Unions role in the holocaust, which is captured in a striking dream sequence near the end of the film where the Jewish family is happily dancing and the moment is cut short as we see the family wearing stars walking with other Jews to what seems to be a concentration camp.

kril10

It is understandable why Commissar was banned at its original 1967 release. Chronologically one of the latest films that can be classified as a "Thaw film," it takes the theme of the "individual over the collective" and extended it into dangerous, perhaps even un-Soviet territory. Despite deStalinization, the Soviet Union and its Communist ideals still stood—the collective was still to be seen positively, and the pure, militaristic attitude of the people was still important. By introducing Commissar Klavdia as an emotionless, militaristic "maiden" with male mannerisms at the beginning, and proceeding to reveal her personal, human side through her feminineness, pregnancy, and change of clothing as she was cared for by a Jewish family, the film interprets the Revolution as a "softening of Communist values." By changing Klavdia from the officer who ruthlessly sentenced a Red deserter to the tribunal at the beginning to being a scared, doubtful mother who seemed unsure of whether or not the new regime would bring "trams and success" when the idea was challenged by Yefim, Commissar, is questioning the validity of Leninism altogether! It becomes a defiance, not a "Thaw" reinterpretation, which is why it likely got banned. Another huge factor to its banning may have been the heavy sympathy for the Jewish faith that it evokes—anti-Semitism was prominent in the Soviet Union even after Stalin. Once it was released under Gorbachev however, the film was allowed to intrigue viewers with its whirling camera shots depicting Klavdia's flashbacks, and its interest in the effects of the Revolution on the psychology of children, by showing how messed up kids got under switching regimes. Understandably banned during its time, but it is a good film about the Revolution nonetheless.

Michael Neumann

The biggest surprise about this little seen Soviet drama (revived in the late 1980s) isn't that it was banned for two decades, but that it was ever made at all. The film is openly critical of the Revolution, but not from behind the fancy metaphoric camouflage used in other repressed Iron Curtain features. Instead, it offers a direct and sensitive story of a dedicated but pregnant Red Army Commissar who, sometime during the 1930s, finds shelter with a Jewish family and is transformed by their affection. In the end she has to choose between motherhood and the Motherland, but her decision to follow military duty does nothing to diminish her new found sympathy for her surrogate family, and before rejoining her company (slogging through an unglamorous landscape of Ukrainian ice and mud) she entrusts her baby to the care of people (and, by extension, a tradition) she has learned to love. Stylistically, the film is a mix of poetic realism with occasionally self-conscious (but effective) montage flashbacks, plus one haunting flash-forward anticipating the Holocaust.

edmontdantes

I was surprised to hear that "Komissar" was filmed in 1967, a year when the USSR was already firmly past Kruschev's thaw and entering the repressive Brezhnev era, because there is something very "thawish" about this film. The general criticism of war, the dignity of ordinary people during a time of calamities, and the juxtaposition of battles with moments of civilian life, all hearken back to the ideas expressed in "The Cranes are Flying" (1956). As in all Soviet cinema, many of the central ideas are expressed through symbolism. This makes the film somewhat difficult for viewers who are not used to this style, but most people tend to find it refreshing and psychologically stimulating. It certainly prompts more post-film discussions than current American cinema that simply shoves the director's point of view down the audience's throat.Some of the themes that I found particularly interesting were: the use of the innocence of children to depict the horror of war, the image of saddled horses without riders galloping into battle, and, of course, the father dancing in the midst of a bomb raid. Most of all, I thought that the change in Vavilova - going from a rough, battle hardened Red Army officer to a nurturing mother, is the most poignant aspect of this film. The scene where Vavilova is hunted my soldiers for having a child mimics her own persecution of a man who leaves the army to be with his beloved. The soldiers turn out to be figments of her imagination, but the point is obvious. However, Vavilova's decision in the end of the film (which I will not reveal for fear of getting blacklisted by the IMDb NKVD) is puzzling in light of the changes in her character. I suppose that Askoldov's opinion that a person's nature cannot be changed by one experience is contrary to my own optimism. Still, I find the end to be somewhat unrealistic.

AD

AD