eddie_baggins

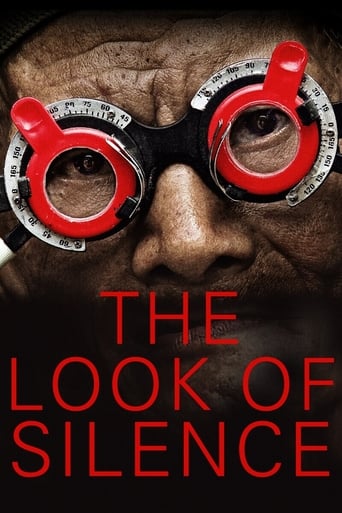

A companion piece to his haunting and unique 2013 Oscar nominated documentary The Act of Killing, Joshua Oppenheimer's The Look of Silence may not have the same gut wrenching impact of his first Indonesian set tale but it's still a highly insightful and quietly powerful look at the after effects of Indonesia's mass killings in the 1965 Communist round ups.Where The Act of Killing focused its attentions largely on Anwar Congo and his fellow death squad members who were responsible for countless murders of their fellow countrymen, The Look of Silence turns its attentive gaze towards average every day optometrist Adi Rukun and his quest to find those that played a part in the brutal murder of his convicted communist brother Ramli.It's a much more straight forward tale than Killing that became something of a fever dream thanks to its subject's willingness to re-enact and portray their experiences through bizarre home made movies and scenarios that had to have been seen to be believed. Oppenheimer this time around sits his camera on subjects and doesn't shy away from the silence of the film's title where questions are raised and eyes and facial expressions say more than words ever could.Rukun himself is also a likable presence and the way in which he deals and interacts with those that were involved with his brothers demise are the film's most powerful. He asks thoughtful and loaded questions and refrains from letting anger get the better of him and Oppenheimer never shy's away from allowing the story to play out without fanfare or manipulation and the true atrocities of what occurred in the beautiful countryside of Indonesia is never too far away from view even if this is very far from being a history lesson in the events.A finely made compatriot of the Act of Killing that would make for a great double bill with its more accomplished forefather, The Look of Silence is not entertainment but it's an important and effective study on war, loss and family and another reason to suggest that Oppenheimer is one of the world's most interesting documentary filmmakers.3 ½ self-illustrated books out of 5

Turfseer

The Look of Silence is Joshua Oppenheimer's follow-up to his fascinating documentary The Act of Killing, which dealt with the legacy of massacres of so-called Communists by paramilitary groups and their followers in Indonesia in 1965. This time Oppenheimer focuses in on an optometrist, Adi Rukun, who goes around interviewing various men and their family members involved in the 1965 massacres, some of whom were directly involved in the murder of his older brother. As in the Act of Killing, the murderers are well-known pillars of their community, proudly boasting about their role in the massacres. Oppenheimer utilizes footage from the Act of Killing which Rukun looks at on a TV screen. In one sequence, the main killer of the man's brother, along with an accomplice friend, are interviewed at the very spot where the brother was murdered. They joke about how they killed the brother which involved cutting off his genitals and slitting his throat.Rukun interviews another killer who soon objects to his "political questions." He cuts the interview off as it's clear he doesn't like dealing with the moral questions that are being raised. The killer is vague about how the victims were identified as Communists. At one point he mentions that they failed to attend the local mosque for prayer services. He also mentions that there were rumors of some people having extramarital affairs which would have implicated them as "bad people." It soon becomes obvious that virtually anyone could have been accused of being a Communist back then. The victims might have been a collection of all types of people from varying socio-economic classes: union activists, non-religious people, those accused by neighbors trying to settle a score, and thousands who were completely apolitical and had no affiliation with Communism.The demented nature of the killers became clear when more than person being interviewed admitted that they drank their victim's blood. They did so, according to these men, because if they didn't, they would have gone "crazy." Family members of the perpetrators often claimed no knowledge that their kin were involved in the massacres. Some of these people stated that the past needed to be left alone and a few even implied that those who persisted in looking at the past could be subject to retaliation in the present day.Eventually Rukun pays a call on his uncle who worked as a prison guard in 1965. The uncle had no guilt feelings as to his role in the massacres and claimed that since he didn't kill anyone directly, he bore no responsibility for the killings. When Rukun informs his mother of this, she's incredulous that her brother may have been involved in the death of her son.In addition to the various killers interviewed, we also meet Rukun's centenarian father who is blind and almost deaf as well as his mother who harbors a great deal of bitterness over her neighbors who have escaped the bar of justice.Between The Act of Killing and The Look of Silence, the former has more of an overall impact. James Lattimer writing in Slant gets to the root of the problem with Oppenheimer's current approach: "With the previous film and most of this one already having repeatedly plumbed the depths of depravity with which such killings were carried out, it's hard to understand why the protagonist needs to be placed in such a manifestly wrenching position, aside from a salacious desire to have his reaction on camera."Despite reservations as to the way the material is presented, The Look of Silence remains a fascinating glimpse into the mindset of people who have committed horrendous crimes and escaped the bar of justice.

MortalKombatFan1

"The Look of Silence" is a companion piece to Joshua Oppenheimer's previous film "The Act of Killing". Both films deal with the mass murder of communists in Indonesia between 1965 and 1966 - a serious crime resulting in the deaths of over a million innocent people by the hands of hired militia sanctioned by the government, but has gone unnoticed in the public eye for so long because the perpetrators are still at large, hailed as national heroes for stopping a revolution and in positions of power in government for over fifty years, living peacefully among the families of those they murdered."Act of Killing" is more audacious in style, following three killers as they recreate their murders for film in any genre they want (gangster flick, musical, etc.) - all the while they're boastful of their accomplishments, without any remorse or regret for their actions.'This film follows Adi Rukun, an optometrist who's brother was murdered in the genocide. We see him confronting death squad leaders and those who knew his brother, looking for some sort of understanding and possibly reconciliation for his murder. There are also domestic scenes with his mother and father, as well as with his wife and family. Life plays out happily before our eyes, but beneath it there are still painful reminders of the past when Adi talks about his brother with his mother, or when he tells his wife what he's been up to, talking with these killers they know. She says she would have stopped him if she knew, that his life could be in danger if he keeps digging up the past instead of forgetting. This gives the interviews a very real sense of tension, and you wonder if such a film could be made if it weren't for the involvement of outsiders who could be there with Adi.Still, Adi puts up a strong front, asking why they did what they did. The answer's usually the same, they deny individual responsibility, or say that it was necessary. Sometimes their answers are disturbing, saying that they drank the blood of their victims to stay sane. Family members of the now-deceased murderer of his brother deny knowing anything about their father's work. In a very affecting scene, Adi's uncle, a prison guard in the army says he was unaware what happened to the detained after they were shipped off onto trucks each day. He's trying to keep up a strong resolve, but you can see the pain in his face when he talks about the past.This film director chooses not to intrude on the telling of the stories with narration, but instead lets the interviewees tell their version of events, leaving pregnant pauses between answers to linger on their faces, which often tell more than spoken words ever could.It's a very quite, slow film, but I found it hypnotic and a damning portrait of a country's silence after horrendous acts were committed. Adi gives a voice to the families of many victims, and both films should be watched by everyone to get a better understanding of the depths humanity can sink to, and how a nation struggles to cope with long dormant pain after government sanctioned genocide.

francescogiacobbe

A compelling and chilling documentary about the shocking Indonesian genocide which saw over 1 million people killed between 1964-1965. The documentary follows an optometrist (Adi) who visits the men who ordered and carried out the killing of thousands of Indonesian "communists" including his brother (Ramli). A follow up to the Academy Award nominated The Act of Killing, The Look of Silence is a defining work in Joshua Oppenheimer's fledgling career and one which marks a significant moment in documentary film. The insights into the human psyche, and the justification of mass murder are both enlightening and terrifying.The Look of Silence is a film about the Indonesian genocide, but more than this it is a study of human conscience, power and ideological and religious beliefs.I watched the UK premiere along with thousands of others in a simultaneous multi-cinema roll out, this was introduced by Louis Theroux and in his introduction he made an apt and insightful point that the film is so fascinating and enthralling due to the natural human inquisition about human nature and specifically about what evil looks like. The ability of regular people with families and, in this case, strong religious beliefs, to brutally murder millions of people, is baffling to the human mind. The questions that flick through your mind when watching this film are not ones that have a single answer: Why would someone do this? How could someone do this?, this film goes a long way to answering these questions. Through the meetings which Adi has with the death squad leaders who ordered his brother and so many others to be killed, there is a total belief by them that what they did was just and right. Never have I seen such unwavering belief in a cause set on destruction.The focus on one mans murder brings the national tragedy into perspective. An often quoted statement by Stalin that 'The death of one man is a tragedy. The death of millions is a statistic' rings true and Oppenheimer has used the tragedy of the murder of Ramli to accentuate the murder of a million others and to show the personal struggle which millions of others have had to go through in the 50 years since the genocide.Many comparisons will likely be made between this documentary and those detailing the Jewish Holocaust in the 1940's, however this is a very different case. The power which the perpetrators of the Indonesian genocide still have within the country allows them the status of heroes and explains the complete conviction of those involved. The "heroes" who are spoken to dehumanise the people they killed talking of them as if animals, they describe with great detail how they killed them often laughing, as if a justification to themselves that what they did was natural and casual. They are free, free from persecution as they hold the power, free from criticism as they instil fear in the people. Through the meetings between Adi and these men, Oppenheimer is able to anthropomorphize them and position what they have done in the realm of understanding. Often with documentary films about atrocities such as this, the perpetrators are portrayed as monsters who have committed unspeakable crimes, Oppenheimer's method of speaking openly about the killings with the people who carried them out gives the film a gravitas not seen since Shoah. This is the great strength of the film, the honesty of it.

AD

AD