Robert J. Maxwell

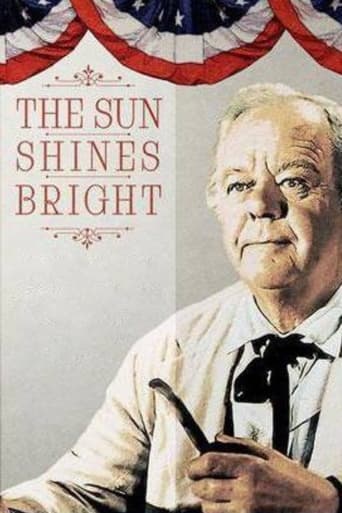

The director was John Ford, a notorious teller of tales. When asked by critics which of his movies he liked best, he sometimes cited "The Sun Shines Bright." To understand why he'd make such an outrageous claim, we must understand that Ford loved to cause disappointment and pain in others -- especially critics.Actually it's a low-budget and confusing jumble of several of Irwin S. Cobb's stories about the laid-back South. Not a bankable name among the cast. But we do get to see the last of John's brother Francis as a tattered old drunk in a coonskin hat, a role he'd been playing for twenty years. Frank had been a matinée idol in the early years of motion pictures, a handsome young hero, and it must have pained him to be so degraded on the screen but, as I say, John loved to see pain.And if you're truly into political correctness, this is an excellent place not to look for it. The judge is the pudding-faced Charles Winninger. He's a fair and courageous judge. Everyone realizes that. But still he has one of those chocolate-colored jockeys holding up a hitching post in front of his gate. That's not to mention Steppin Fetchit: "Yassuh, Boss, but you overslepp." But it's certainly a John Ford project. Many of his stock company put in their appearances: Jane Darwell, Jack Pennick, Russell Simpson, Grant Withers, Milburn Stone, among others. We even get to see an early work of John Russell and the teen-aged Patrick Wayne. Russell is a curious-looking guy. He was an intelligence officer on Guadalcanal with the Marine Corps and he looks it -- tall, brawny, handsome. But handsome in a way that's uncanny, unearthly, as if he were really an animated plastic mannequin.It's definitely a lesser work, by turns raucous and sentimental. Ford pulls out all his usual stunts and throws them haphazardly together. There's the grand march, the singing of hymns, the mano a mano fight, the Ladies Temperance Society. If you want nothing more than to sit back and be diverted for an hour and a half, this should do the job.

antcol8

Who is up to the task of writing about this film? It wears its contradictions on its sleeve.It encompasses more than one can ever hope to clarify. If discussions about it bog down to "It's a racist film" "It's not a racist film" can anyone be blamed?The film is so much more than its racial attitudes, and yet those attitudes form the loci of all points of agreement or disagreement about what this film wants to say, or says, or means.The subject of the film is SOCIETY: the social contract, what holds it together, how an individual situates himself within a societal fabric. How important it is for a society to preserve its unique It-ness in the face of encroaching homogeneity. How all this is a balancing act, a tightrope walk. Is there such a thing as "equality", and how can one determine what that is in the face of so much DIFFERENCE? What does it mean to speak of strata - levels - different kinds of societies existing as part of one society? We encounter so many kinds of difference: Blacks, Whites, former Confederate and former Union soldiers, rich, poor, Men, Women...all living together in some kind of fractious unity.On another level, though, the film can be read as nostalgia for a time when Blacks knew their place, and colluded in a "special relationship" where tolerant, "humanistic" Whites would recognize the vulnerability of the Blacks' social status and take on the role of "protector". Where this would require the Blacks to freely and happily participate in their infantilization, and where they would fulfill the important function of adding depth or "soul" to all rituals and celebrations. All would recognize the unique commingling of joy and sorrow in Black song, and none would try to compete, knowing full well that this was one domain where Blacks were sovereign.We see no Blacks voting. Are they forbidden to vote? The film is very slippery on this point. When US, the Black banjo virtuoso saved from lynching tells Judge Priest he'd do anything for him, Priest replies "I know you would, son, but you're too young to vote!". Does Ford think the Blacks in 1905 Kentucky were too YOUNG to vote? Do women vote in this movie? Do you care?Are we giving the ideas in this movie too much WEIGHT? The movie is meant as ENTERTAINMENT, isn't it? Well, let's look at the long scene of the whore's funeral - entertaining? Not really.What is this long, mostly silent scene? Why is it so privileged formally? What does Ford want the viewer to get? Something about dignity. Something about the need for the individual to take a stand and - through ACTIONS and not through WORDS - compel a community to recognize and confront its deep - seated prejudices. Ford makes the point eloquently.But there is something dangerous in this "cult of personality". Judge Priest wins the election by the barest of margins. He is aging and tired. Probably he'll lose the next election, if he even runs. Actual LAWS - WORDS inscribed in BOOKS - are also fragile, and can be defeated and overthrown. But they can potentially give a little more solidity to Social Change, no?Ford waits a long time before confronting the ambiguity of the kind of personality who operates ethically while maintaining - and not in any real way challenging - the Status Quo. It's not until The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence that individual action (the Wayne character) is contrasted with a belief in the power of LAW (the Stewart character). And where does Ford leave us with this? With a lot of questions...Ford is very sentimental. It's not very hip or cool. Everything is pushed to the point where a prostitute shows up just in time to see her abandoned daughter, right before dying. And all kinds of symbols - paintings, songs, etc. - connect to this event, gesturing towards the past, acquiring tactile significance. The stoic former Confederate leader is compelled to recognize this prostitute as the mother of his heretofore unacknowledged granddaughter. All of this generates the film's emotional high point.Ford is often called the Poet of Lost Causes and maybe we should cut him some slack and accept that this attraction to Lost Causes explains what seems to be a preference for the Confederate characters...or maybe we shouldn't.I love this film. I love its hermeticism. The fact that Ford is so out - of - date that he has Stepin Fetchit babble on in his insanely personal dialect when the entire civilized world was (slowly) headed in another direction. This film might be both Conservative and Radical but one thing it ISN'T is Liberal! No wonder the NYTimes hated it...It is a work of art. No wonder Ford loved it.Andrew Sarris questions whether it deserved the care it was given, and suggests that Ford should have treated it as one of his throwaways. Nonsense! Real artists are quixotic, never knowing which project "should" be the more loved one. That's why we need critics. But what am I saying? Ford was right about this one.

JoeytheBrit

It would be nice to be able to discuss this film without having to refer to its politically incorrect depiction of blacks, but it's impossible to do so. The film, which is a remake of director John Ford's own Judge Priest from the 30s (in which Will Rogers played the title role), must have seemed curiously dated even when it was released, and feels like it was made in the early forties rather than the mid-fifties. Whether that's because of its outdated attitude towards blacks and the presence of slow, scratchy-voiced Stepin Fetchit is open to conjecture – it could just be that the fog of nostalgia that hangs over the entire work is the reason.Charles Winninger makes an amiable old judge whose quiet wisdom puts to shame the hypocritically puritanical attitudes of his small town's people and the racist assumptions of an unruly lynch mob out to hang a blameless teenage Negro. The storyline is kind of meandering, reflecting the apparently relaxed pace of life in the turn of the century Deep South, and you do really get a taste of Southern gentility – whether accurate not. Its various sub-plots are linked together by the judge's bid for re-election, which serves to emphasise the importance of standing by one's principles no matter what the possible personal costs may be. Of course, the truth is Billy Priest is too good to be true, but I don't think anyone was out to make him a more realistic figure in this milieu than Santa Claus or God would have been.John Ford's notorious sentimentality is in danger of becoming cloying at times, but he just about manages to rein it in at key moments. The film says as much about Hollywood's take on American social attitudes in the mid-50s as it does about the same in the Deep South at the turn of the century, which isn't in itself a bad thing. I suppose it's even possible that one day films like this will be shown in classrooms to demonstrate the gigantic positive strides made in the cause of racial equality in the latter half of the 20th Century. Better that than they are wilfully ignored in the name of political correctness.

fisherelle

One of the odd aspects of this film is the post Civil War background that looms large to a greater or lesser degree throughout. This takes the form of a blatantly obvious pro Confederate stance, and an almost religious idolatry of 'Dixie'. Halliwell tells us that Judge Priest, the moral heart of the film, "has trouble quelling the Confederate spirit" - but the opposite is the case - the judge is absolutely central to maintaining and celebrating that spirit. The oddness comes because, it seems to me at least, we are not used to seeing such a character defending black rights, preventing a lynching, etc. Even more peculiar is to see such a 'happy' black population - particularly the quite disturbing courthouse scene where 2 black characters suddenly burst into a grotesque song and dance routine. "Mississippi Burning" this certainly isn't! But certainly a film worth watching, and the prostitute's daughter's funeral scene is excellently done. It somehow feels older than 1953.

AD

AD